Living with loss and grief in a care home during these times is a part of the every-day experience for carer, staff and families.

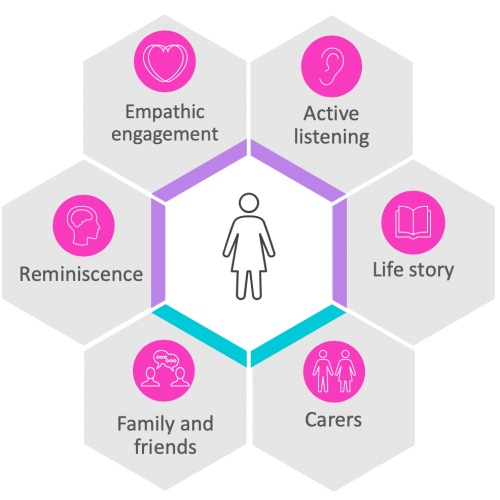

For anyone who is working in the care sector may need a bit of extra support at this difficult time. We asked therapeutic counselling specialist for people with dementia and REAL Communication Works advisor, Danuta Lipinska, to share some of her own experience and wisdom about such things.

In this article, you will find lots to reflect on and useful suggestions that can help you through this challenging time.

Caring for frail older people or even younger people with life limiting conditions or mental health concerns and physical disabilities or a dementia, you will not be a stranger to the ongoing nature of dying and death, loss, grief and mourning.

Care staff often say to me, “Well, it’s just part of the job. We do the best we can, and we usually don’t let it get to us too much.”

But this is not just the job as usual. So why is it different this time? The nature of this pandemic brings us into the realm of Traumatic Loss.

This means that there is a deeply disturbing threat of actual or possible harm directly towards you, your loved ones, those you care for at work and the citizens of the world at large. Feeling frightened and anxious are natural human responses to trauma and the threat of trauma.

Fear of breaking down and losing control are also common..

Caring for residents with the illness, wondering when the next person will become unwell and supporting their death and dying, knowing that what we have done has not been enough in this case brings feelings of inadequacy, guilt, hopelessness and helplessness, great sadness and anger.

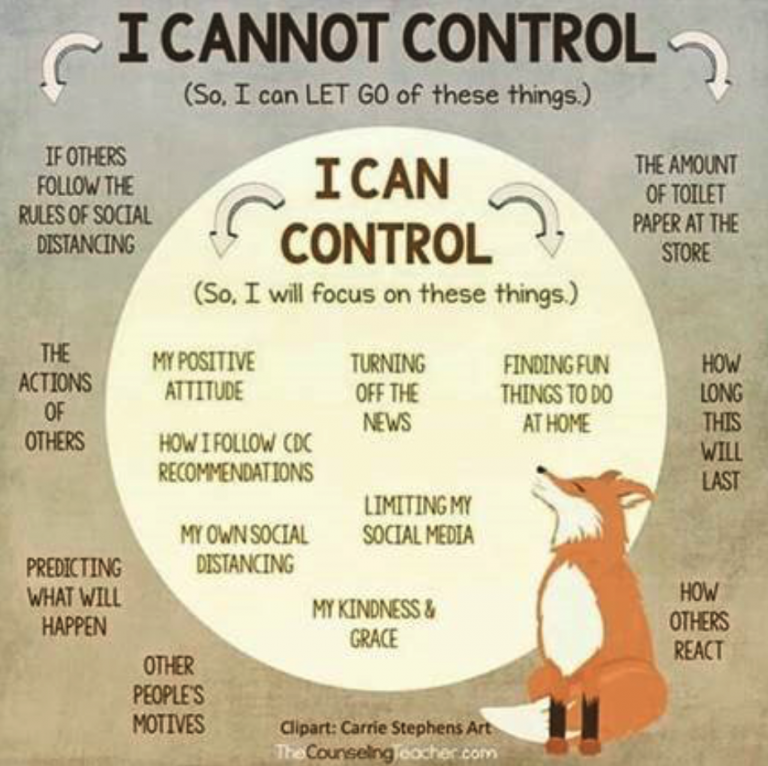

The losses associated with the Covid-19 pandemic arouse our basic instincts to threat and we respond in the instinctive way (our ‘gut response’) is Fight, Flight, Freeze or Follow (you can find out more here). We feel the loss of how things used to be in our care home and may feel powerless to change it.

Living with loss and grief in a care home is having a profound effect on the residents and many more of the women and men who live there are becoming unwell.

Some are going to hospital and not coming back, and some are dying in the home. You wonder if their death could have been prevented. You may not have had the chance to say goodbye to a person you have come to care deeply about over many years. Relatives, partners, children, grandchildren are not able to be with them as their illness progresses and their dying and death takes place.

You are responding to multiple losses – many losses at once. At work, at home, in your families, in the community, the country, the world. You have had to take on the management of the multiple changes within the care home that would not normally be occurring. Even if you have had an earlier quarantine event that required the home to shut down and relatives could not visit, you would have had an ending in sight when things could return to normal. At the moment we don’t know when the end might be.

Our basic needs for security and safety have been threatened. For some people, food and shelter, jobs and finances are affected. For many, their sense of wellbeing and being able to cope has been challenged and they are not themselves. We were unable to prepare for this and this can leave us feeling de-skilled and vulnerable.

Loss

Loss (or bereavement) is what happens as a result of the changes in our lives or the actual death of a person or pet.

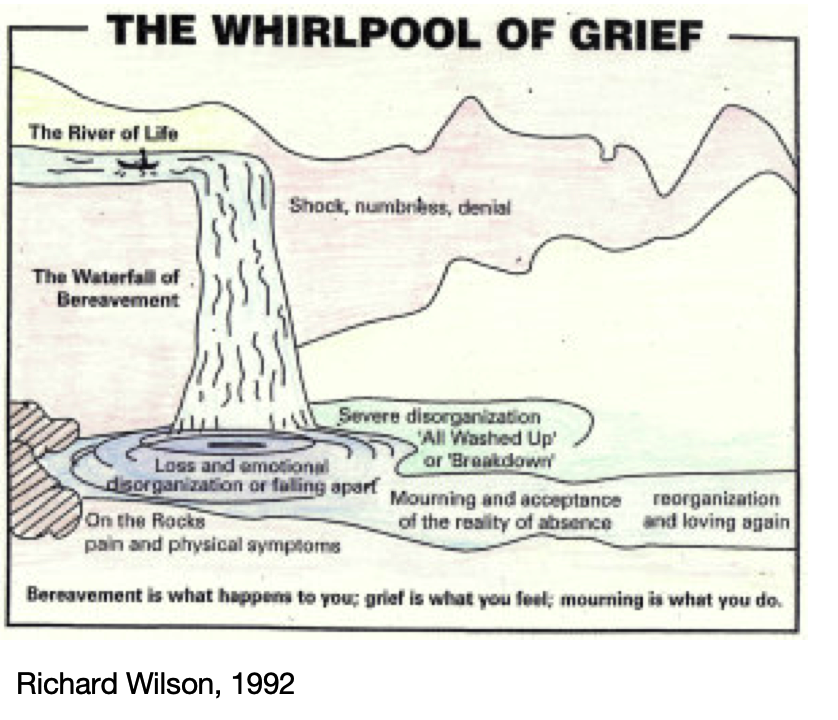

Loss is the event that happens when we are rowing along the River of Life in our canoe and suddenly, we are thrown over the edge into a waterfall and the swirling whirlpool below. Along the way, over by the rocks there is a calm deep pool. We could end up in either or both of these places.

The losses associated with the Covid-19 pandemic arouse our basic instincts to threat. Our needs for self-protection and survival kick in and we respond in very basic human and instinctive ways (our ‘gut response’) Fight, Flight, Freeze or Follow.

Grief

Grief is what we feel and this can be a ‘whirlpool’ of many emotions all churned up and colliding with and washing over one another, or a quiet still pool where feeling numb and non-reactive is just another way of being with the loss. It is a process of stages that can come and go, co-exist and last for as long as we need them to. There are many ways people have written about grief. Possibly the most recognisable is the Five Stages of Grief described by Dr Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in 1969. They are Denial, Ange, Depression, Bargaining and Acceptance.

It is important to remember that we all grieve in our own unique way, and these are just guidelines that might help to make sense of your experience. If it doesn’t, that’s fine. Something and somebody else will be there to help you, if you ask, when you are ready. That might be tomorrow, it might not be for a long time.

At this particular time, it seems to me that there are a few kinds of grief that we are experiencing within this pandemic.