What is the person saying?

By Sarah Reed

How facemasks affect how we communicate. The importance of emotional perception, expression and reciprocity in non-verbal communication is bound to impact the outcome of any doctor/patient or carer/cared-for interactions.

Studies have demonstrated the impact of doctors’ and carers’ empathy and person-centred care on the enablement and health outcomes for the person in receipt of care with both chronic and acute conditions. In a large randomised controlled trial in 2014, it was found that the “wearing of facemasks by doctors had little effect on patient enablement and satisfaction but had a significant and negative effect on patients’ perceptions of the doctors’ empathy”.

We must hope that eventually, mask makers will recognise that clear panel masks are really the only ones worth using and start manufacturing them. However, in the meantime, the following tips are good for all our interactions with anyone at any time whether they have dementia or not, but are especially important now with the additional social distancing that masks create.

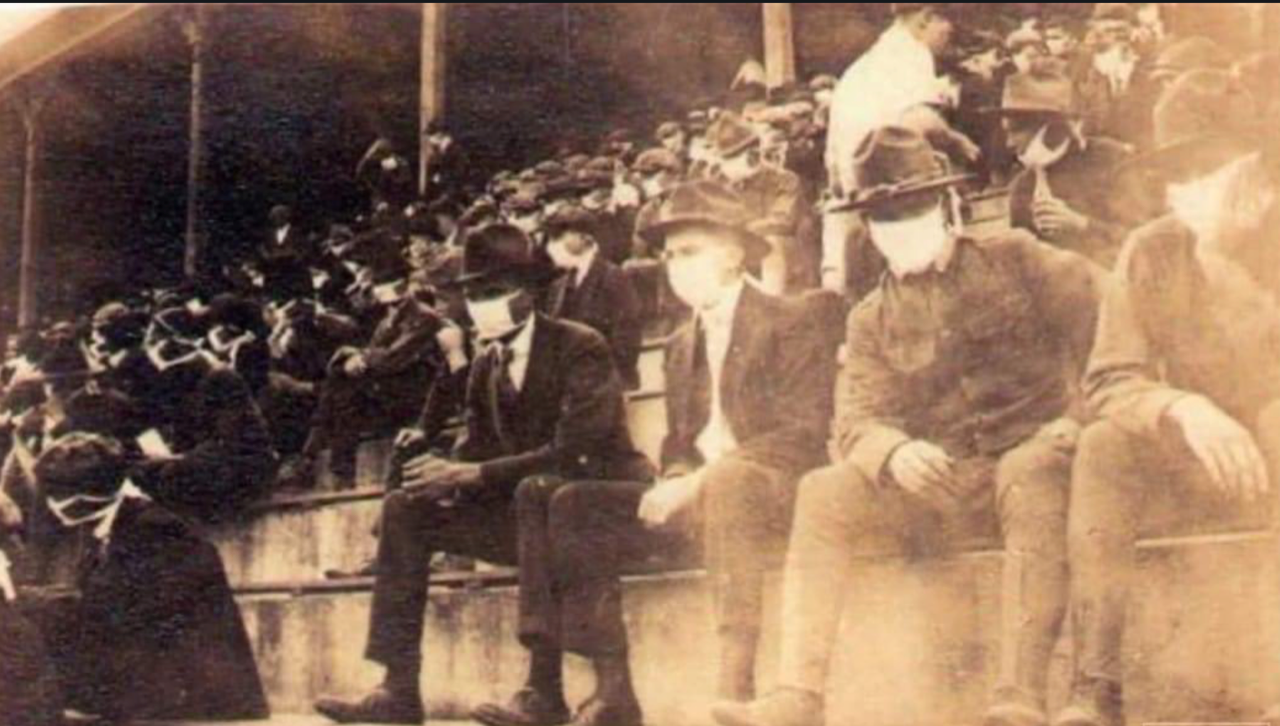

In communication, most of us rely on language – often at the expense of many other types of communication. However, nonverbal communication is just as important as the words we use. During these times of the Covid-19 pandemic, the use of facemasks has become ubiquitous and they present serious communication difficulties which should not be under-estimated, for the wearer and the person they are talking to, alike.

Lockdown is one thing, but facemasks are prisons that limit the range of our actions and words.

In covering our facial expressions, face masks hide our emotions. For example, pleasure, sadness, frustration, annoyance and fear are all emotions that we show on our faces without ever having to say a word. And unspoken communications tend to be the same across most cultures. Given the increasing use of facemasks, this means of communication is becoming increasingly challenging.

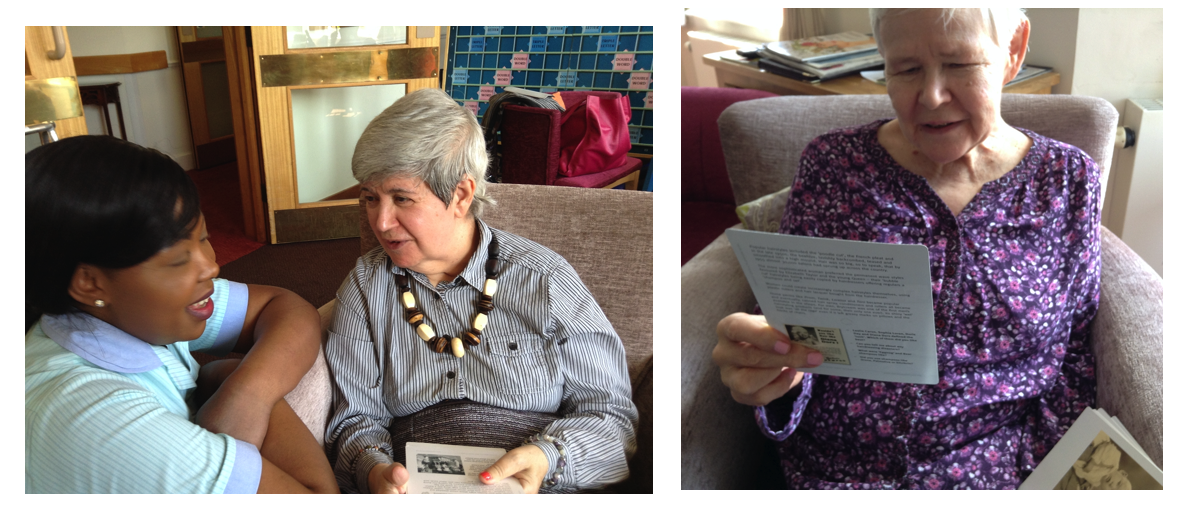

Non-verbal communication is often the most effective element of communication when connecting with a person who has limited or impaired cognition or is living with dementia. People with dementia increasingly lose their ability to communicate verbally, but their body and para-linguistic interpretive skills are retained longer in most conditions and may even be retained right to the end of their life. They are usually able to interpret facial signals correctly and can be skilled interpreters, understanding when we are relaxed or stressed or conveying other subtle messages, making sense of things from the sound and inflection of our voice, our speed of speech, our posture and the way we move around. We know that when people have difficulty understanding, they will fill in the gaps by reading our facial expressions, the sound of our voice and body movements and posture.

Carers who are more alert to nonverbal cues are often well-practiced at reinforcing the other person’s perception of their sincerity, compassion, appreciation, dedication and competence. This improves their relationships with those they care for as well as their colleagues and also increases their ability to provide meaningful care.

Nonverbal communication provides unique opportunities to connect, so it is important to pay greater attention to our nonverbal communication in this time of social distancing and masked faces.

The following tips can impact and improve interactions with older people while wearing masks. Being focused on the challenge of this is key to success.

1. Pause and be mindful. Be self-aware

If things are busy and stressful, try not to let that be reflective in your voice. Make sure there is enough time for any interaction. Taking a moment or two for yourself immediately before an encounter can make a big difference to the experience. Creating a mental ritual to focus your attention before seeing someone, can help. For example, reflecting on the many varieties of communication that older people and their carers encounter in care settings, such as expert-layperson, healthy-sick, independent-dependent, cognitively healthy–cognitively impaired, young-old and family and so on, might be an option.

2. Be Calm. Smile inside – and outside

Show absolute respect. It is essential to approach the person from the front. This will help them to process who you are and what you are saying. Respect the person’s personal space and make sure you speak to them on the same eye level.

Good eye contact is most important. Use your eyes and eyebrows. Let your eyebrows tell the story. Remember to smile! The person may not be able to see your mouth, but they will be able to read the emotion in your eyes which will allow them to feel more comfortable and in control. They are very likely to be able to detect your body language, so remember that any sudden movements can cause distress and make it harder to communicate.

Be straightforward and try to stay calm. Project a positive, calm attitude and avoid any body language that shows frustration, anger or impatience. Try not to interrupt them and give them your full attention. Be flexible and patient.

Don’t just rely on giving information verbally. Using images, gestures, even written words, phone translation/text apps can be helpful. If the person is still able to read, it may be useful to leave any written version of verbal information that you use with them, so that they can refer to it later.

3. Speak clearly

Avoid noisy environments that might overwhelm with additional stimulus. It is useful to remember that 11 million people in the UK have hearing problems or are deaf. There are a number of hearing apps available on the market which can help. Firstly, create a safe space. and maintain your social distancing with a clear path. Ensure that any physical barriers that could block your view or further challenge your voice being heard behind the mask are removed.

Observe first, even if briefly.

Remember to smile! Always ensure that the older person is wearing their glasses or hearing aids. Your tone of voice includes your speed, tempo and pitch which can be as impactful as the words you are speaking.

Slowly communicate one point at a time. Use short, simple sentences and underline your words with appropriate gestures. Make your statement or ask your question and then pause. Keep your voice even, gentle in tone, and moderate your speed of speech. Go slow!

Lip-reading cues that many with hearing disabilities use to compensate will be absent, so make sure you articulate your words clearly without sounding forced, which may be taken as condescension.

Consonants matter! Speak louder if necessary but without raising your voice or its tone, because this might be perceived as aggression. Using NLP (Neuro Linguistic Programming) techniques of mirroring and matching the person’s gestures, vocal tone or mood can be re-assuring for them and help them feel better understood.

The messages we convey might be harder to interpret so we need to develop new habits, ensuring that we underline everything we say with gestures and pantomime. Going slowly with the person will make connection easier.

4. Remember to listen well

Listening is a vital part of communication as well. Making space to listen is very important in any encounter. However, in one randomised trial in 2010 it was found that “64% of the nurse participants had a weak knowledge of verbal communication skills and only 36% had relative knowledge about listening and speaking skills. This is while verbal communication skills are considered as the foundations of communication in everyday life”. your view or further challenge your voice being heard behind the mask are removed.

Observe first, even if briefly.

Remember to smile! Always ensure that the older person is wearing their glasses or hearing aids. Your tone of voice includes your speed, tempo and pitch which can be as impactful as the words you are speaking

5. Remember that our bodies speak as well

It is vital that we think about the ways in which we typically communicate, such as gestures and tone we use when we are not inhibited by distance and PPE. Once we become more aware of our characteristic gestures and body language, it is easier to align our nonverbal signalling with our spoken message.

Body language is vital to deliver meaning well and communicate effectively. Together, hand gestures and posture are very important. Our non-verbal cues should send message of kindness and empathy. Try to relax your shoulders. Remember to avoid crossing your arms in front of your body and keep your hands off your hips and out of your pockets.

It is always helpful to nod and add ‘mm’ and ‘yes’ when appropriate, as it acknowledges that you are listening and understanding.

Happiness can be seen by raised eyebrows, raised cheeks and crow’s feet. Remember to smile! On the other hand, eyebrows pinched together and eyes drooping can indicate sadness and when in a “V” shape can express anger.

The person with cognitive impairment may not recognise you at all in any encounter if you are wearing a facemask, even if they have spent time with you over many months, but we still need to make each connection count. As one wise soul once perceptively observed, “I may not remember what you said, but I will remember how you made me feel.”

Facemasks and perception of empathy

Here is an article from NCBI – US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. It is regarding a randomised control study that was conducted to explore the effects of doctors wearing facemasks on patients’ perception of doctors’ empathy, patient enablement and patient satisfaction.

The report can be viewed here and it is titled ‘Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care’

About Sarah Reed

Sarah Reed is the founder and lead at REAL Communication Works.

Sarah lectures in Health departments at Kingston and City Universities. She now works with other highly skilled dementia care learning facilitators to deliver interactive REAL Communication workshops.

She has served on the SUCAB Service User and Carer Advisory Board in the School of Health Sciences at City University since 2017.

She is a Trustee of and thirty-year volunteer co-ordinator and monthly driver for national older people’s charity, Re-Engage (formerly Contact the Elderly). In 2015, she served on NCVO’s Volunteering in Care Homes advisory board. She is a member of the DH Quality Matters board.