I recently tweeted that SCIE have great resources – and here’s why:

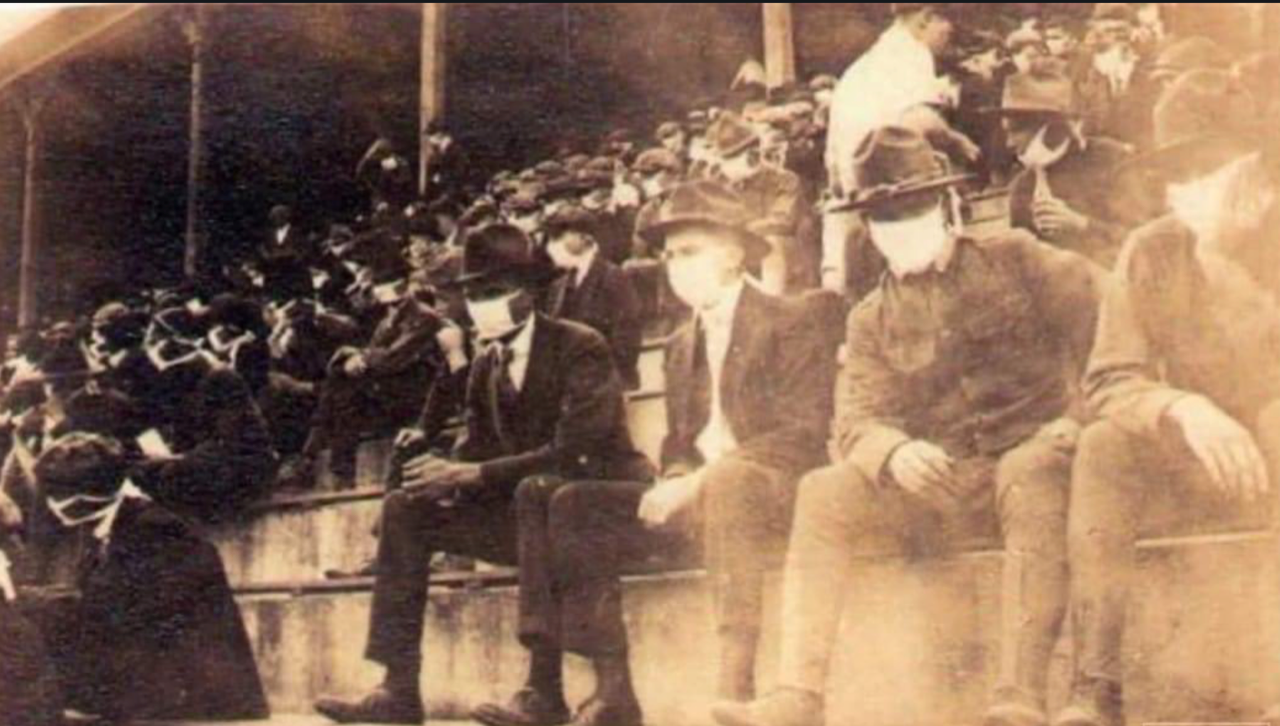

We’ve just celebrated Carers Week 2013, and it’s important to remember that getting anything right in meaningful dementia care for a person can be a challenge. The cognition, awareness and linguistic goalposts are continually on the move and the very personal and unique nature of the condition is challenging.

Help is at hand. The lovely people at SCIE have invited me to write this opinion piece after I tweeted “@SCIE_socialcare is probably THE best care resource on the web – excellent in every way! Thank you.”

I really meant it. The resources on the site are extraordinary. Want to know more about reablement? They’ve got it. Need guidance on how carers can work with care staff over dementia care? This is where you’ll find it. Keen to up-skill yourself in co-production? Here’s the seminal advice.

SCIE has gathered a stellar group of care specialists and persuaded them to share their deep experience and knowledge on a wide range of subjects, which any carer can use whether working professionally or in an entirely domestic setting with a family member of friend. This is where you’ll find some of the most expert trainers.

I publish Many Happy Returns’ “conversation trigger” Chatterbox 1940s and 1950s cards for people with dementia; I also run REAL Communication Works™ skills development workshops, to promote better interaction with people with dementia for health and social care care-givers, and University students. The participants are often thirsty for knowledge and it’s great to know that I never need to swamp them with paperwork to support the programme. I just point them in the direction of the SCIE website. Job done –and a few trees saved, into the bargain!

And when writing articles or developing other resources of my own, it’s vital to get it right in every respect, so the SCIE website is my first port of call to check that my point of view is supported and endorsed by the best of the best-practice experts.

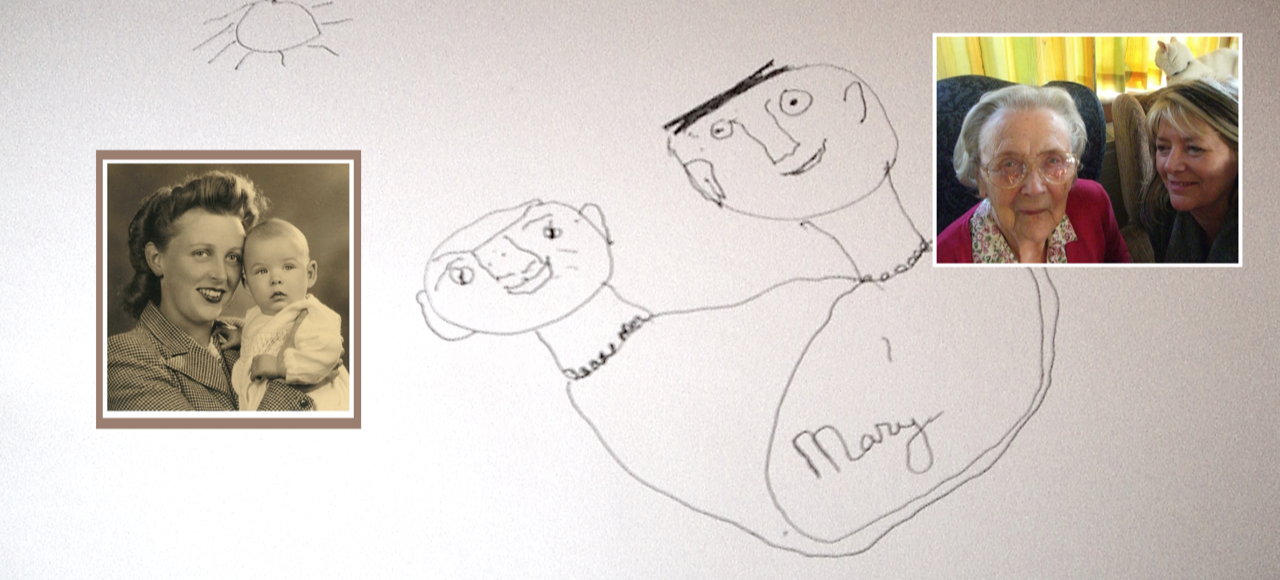

SCIE always remember the people they serve – the people who use services and their carers. It’s good to be reminded and as growing numbers of people are caring for their families at home, this is more important than ever. Here’s the story of one such couple; they happen to be my parents.

My Dad was a stiff-upper-lip kind of man

When a loved one develops dementia, those closest to them are likely to experience feelings of confusion themselves, as well as anxiety, guilt, grief and bereavement – even before the person dies, as the illness progresses.

No sooner do they come to terms with one stage of the loved one’s illness than the person’s behaviour changes again or their cognition declines further and the grieving starts all over again. A sense of loss is one of the most powerful feelings that people experience when someone close to them develops a dementia.

My father spoke about this with me on a number of occasions during the decade that my mother had dementia. Had SCIE been in existence at the time I know how it would have helped us.

He said that not only had he lost the person he had married in 1940, he’d also lost their future together. He missed the years of happy companionship they’d enjoyed, but equally, he was frustrated by the constraints on his freedom.

After three years at home, my 85 year-old mother was admitted to a care home. For my father, whilst relieved, this rendered the family home an empty vessel, with only the ghosts of their former lives for company. Of course my mother’s life was hardly better, coping with an utterly different and mystifying life, in the company of strangers.

My father seemed overwhelmed by sadness and anger. I noticed his underlying resentment and unhappiness that things had not turned out as he hoped. He was lonely and isolated and he worried a lot about the potential cost of ongoing care.

Unable to recognise that he was under a lot of stress and unable to to ask for the emotional support he needed, he would bottle up his feelings. He began to weep openly.

We encouraged him to spend time with friends, but he found it difficult to do things that would normally have included my mother. He tried to muster his old energy, but without his beloved partner of sixty years, he gave up.

A few years on, after a short illness and three years ahead of my mother, he died.

“Who’s in that box?” she asked at the funeral.

Sarah Reed is a dementia communication specialist and trainer; and founder of social enterprise, Many Happy Returns