“A diagnosis of dementia for a person is also a diagnosis for the whole family.”

Anon

Dementia can be very hard to come to terms with. Hard enough for the person diagnosed of course, but also hard for family carers, who must watch the relentless deterioration of the person they love, usually over many years, with no hope of reversal. They must also adjust their own behaviours accordingly. In many ways, dementia is a slow, ongoing bereavement process, of loss of a loved one before the person’s death and often means massive and often exhausting changes to the carers’ own lives.

Dementia can be scary and disorientating for the person with the diagnosis, often including

- short-term (working) memory loss

- gradual loss of awareness of basic things like eating, drinking and personal hygiene confusion as to their whereabouts or who people are — who they may have known for much of their lives

- loss of life skills like reading, language and vocabulary

- rapid mood changes, anxiety, depression

- depleted motor skills and mobility,

And that’s just for starters.

All these aspects of dementia can be frightening, frustrating and mystifying for the person and saddening (and sometimes maddening) for relatives.

And just when things may seem to have settled into a steadier pattern, the person’s condition may decline further and the care goal posts will move yet again.

Despite this long and pessimistic list — and even though dementia cannot be cured or reversed, our own behaviour can make a big positive difference.

A person can live well with dementia for a long time and with changing attitudes in dementia care, the experience does not have to be unremittingly negative

Happily, in recent years, good communication is slowly being recognised as one of the most important and essential ways of helping the person with dementia and their family to deal with the condition.

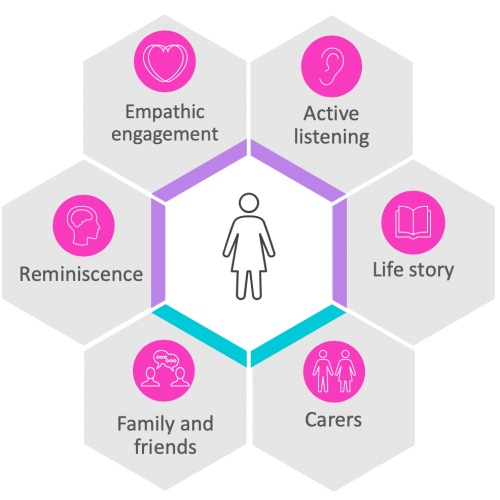

I developed the REAL Communication Framework in 2003 as a response to my own observations, worries and concerns about my mother’s condition and her care. The four letters of REAL stand for Reminiscence, Empathic engagement, Active Listening and Life Story. These are the four letters create the four pillars of good communication with a person living with dementia.

Mum had vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease for about ten years. I had noticed how her friends gradually fell away, how people were nervous to engage her in conversation or worse, ignored her and spoke through me. I had noticed how impatient my father could be with her sometimes, the woman he adored and had lived with happily for over 60 years — and how all of us in the family felt ‘at sea’ with the experience.

Here is the REAL framework, which surrounds the person with connection and meaningful communication – and all from four letters.

Dad wasn’t coping and Mum found herself in a care home. I noticed that the other residents and their families had some similar issues to our own. I saw that Mum was increasingly challenged to express herself. Of course, the carers knew almost nothing about her and had no tools to help them get to know her better.

First off, I made her a life story album ‘This is My Life’ to help them (and me, as it turned out) to get to know her a better and to give her opportunities to be the expert, in remembering and talking about her life.

Unexpectedly, it became the most important item in her life. Nothing fancy, you understand, just a pictorial chronology of her life with some simple autobiographical captions; for example, “Me in the garden dancing”, “Our honeymoon in Bournemouth”, that sort of thing. We looked at and enjoyed the family photos continually over the seven years she lived in a care home.

I was on a voyage of discovery and she was sharing her experiences as a girl and as a younger woman, — memories I knew very little about, a person who seemed so familiar, yet I hardly knew.

In finding out about her youthful years, we bonded more deeply. This growing closeness helped me to understand better what she might want in the here-and-now. Like all of us, her outlook, needs and expectations had their foundations in her earlier life.

We would watch DVDs together which I knew would make her laugh. In the earlier days we might watch episodes of one of her favourite comedy TV programmes like Dad’s Army. Later, she couldn’t follow the plot lines and even Arthur Lowe’s pompous disdain no longer seemed so funny. Then we moved on to The Marx Brothers.

Nothing like a bit of slapstick for some instant shared hilarity. Her favourites were A Night at the Opera and Duck Soup…

On warm days, we might sit in the care home garden in the sunshine and talk about the birds and bees and flowers and trees and remember her tending the garden at home (mostly endless weeding) and chuckle about Dad in what was his favourite haunt, wearing nearly threadbare gardening clothes.

And while she still could, we talked. About growing up and then bringing up four children, about the hard labour of housework, about life during wartime and dad’s ‘courting’. I admired her endless capable creativity in the house and her delicious cooking. Through sharing her reminiscences and with some empathic, concentrated listening from me, over time, she seemed to be more settled in the confusing, wobbly world she found herself in — and the long list of negatives seemed just a tiny bit shorter.

When these four letters R-E-A-L are in place, anyone can have an easier and more meaningful relationship with a person with dementia and help make it an experience that can be borne more lightly by all.

You can learn more about the REAL Communication Framework and how it helps to transform the lives of people living with dementia and their caregivers here>

No comment yet, add your voice below!