Age UK Statistics

1,000 words from Age UK on the statistics that should alarm and shame the country

This report comes from Care Industry News on 9 February 2020. Sadly, it makes pretty depressing reading.

1,000 words from Age UK on the statistics that should alarm and shame the country New Age UK analysis finds that in the last 12 months, about 700,000 requests for formal care and support, equivalent to 51% of all applications, have been made by older people and yet have resulted in them not receiving formal care services.

This is equivalent to 2,000 claims from older people being unsuccessful each day, or 80 every hour. In some of these cases, the older person was found by their council not to meet the eligibility criteria set for the social care system, and that was the end of it (23% of all requests for help); while in others the older person was found ineligible, but their council then referred them onto other services in the hope that they could assist, including their local Age UK (46% of all requests for help).

The charity says that these figures show how very difficult it is now to qualify for care within our shrunken social care system: between 2010/11 and 2018/19 total spending on adult social care fell by £86 million in real terms, representing a 4% reduction in local authority spending. While spending has now mostly recovered from its lowest point in 2014/15, the older and disabled population has meanwhile significantly increased, meaning social care spending per head of the adult population has fallen by 6% per person over the same time period. Because councils are so stretched, it is very concerning but not at all surprising that so many older people who are asking for help are being turned away.

Age UK’s new analysis also helps to explain why the numbers of older people living with some unmet need for care are so high and continuing to rise: 1.5 million over 65s in England are going without all the help they need to carry out at least one essential ‘Activity of Daily Living’. If you ask for help from your council and are turned down for it and you don’t have family or friends to step in or enough money to fund your own service then you are likely to find yourself included in this growing army of older people who are soldiering on unsupported, despite having some need for care.

Age UK is drawing attention to these findings as it publishes a new report highlighting the battle that older people and their families often face in trying to secure social care. In ‘Behind the Headlines: Battling to get care’, the Charity describes the social care system as being “woefully inadequate for the job now required of it, despite the best efforts of the good people working in it.”

Over a fifth of all the calls to Age UK’s information and advice line concern social care, a figure approaching 35,000 last year. The report draws on the content of these calls and recounts the very difficult experiences older people and their families are going through as they try to secure the help with everyday tasks like washing, eating and toileting they badly need.

Caroline Abrahams, Age UK’s charity director, said: “The fact that 2,000 older people are being turned down for care every day demonstrates both the enormous numbers impacted by our ramshackle care system and how serious the problems it faces have now become. We don’t know what happens to these older people whose applications are rejected, but inevitably some have no choice but to struggle on alone. Good social care helps to keep older people fit and well, so if you are forced to go without it’s a recipe for emerging health problems to turn into crises, possibly leading to a hospital stay that might otherwise have been avoided and a decline in your health from which you may never fully recover.”

“Faced with too much demand and too little supply, our social care system is effectively under siege. Councils do their best with the resources they have but there are simply not enough to go around. One result is this vast number of older people whose applications for help are rejected and another the long waits for an assessment to have your case looked into at all. Our report is heart-rending stories of older people in need who are being comprehensively let down, and the nightmarish situations created for them and their families. Real suffering is going on, with older people’s lives being diminished and, in some cases, we fear, being cut short.”

“The Prime Minister has promised to fix social care, and our new report shows why it’s so vital for our older population that he keeps his word. For some, tragically, it is already too late.”

Mike Padgham, Chair of the Independent Care Group, said: “The Age UK statistics are alarming and shame us as a country. They should make the Government sit up, listen and act – beginning with ploughing more money into social care in next month’s Budget.

“Some £8bn has been cut from local authority social care budgets since 2010 so it should not come as a surprise that more and more older and vulnerable people – our mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters – cannot get the care they need to enjoy a basic, decent quality of life.

“In 2020 it is a national disgrace, degrading and dehumanising and action to solve the crisis in social care is long overdue.

“We have total sympathy with local authorities who have had their budgets cut savagely in the past decade to the point where they can’t deliver care to those who need it most.

“Now that key milestones in Brexit are out of the way it is time for the Government to turn its attention to the number one domestic priority – social care.

“Boris Johnson promised to sort out social care ‘once and for all’ when he became Prime Minister and again at the General Election, but all we have been promised is ‘cross-party talks’ and a solution within the five years of this parliament.

“Well, as these figures demonstrate, we cannot wait five years. There is no time for more talks and reports, we need to get social care done now, and the Government must start by pumping funding into care at the Budget. At least £8bn extra is needed, just to reach the levels we had in 2010, and we need to go much further than that so that everyone who needs care can get it.”

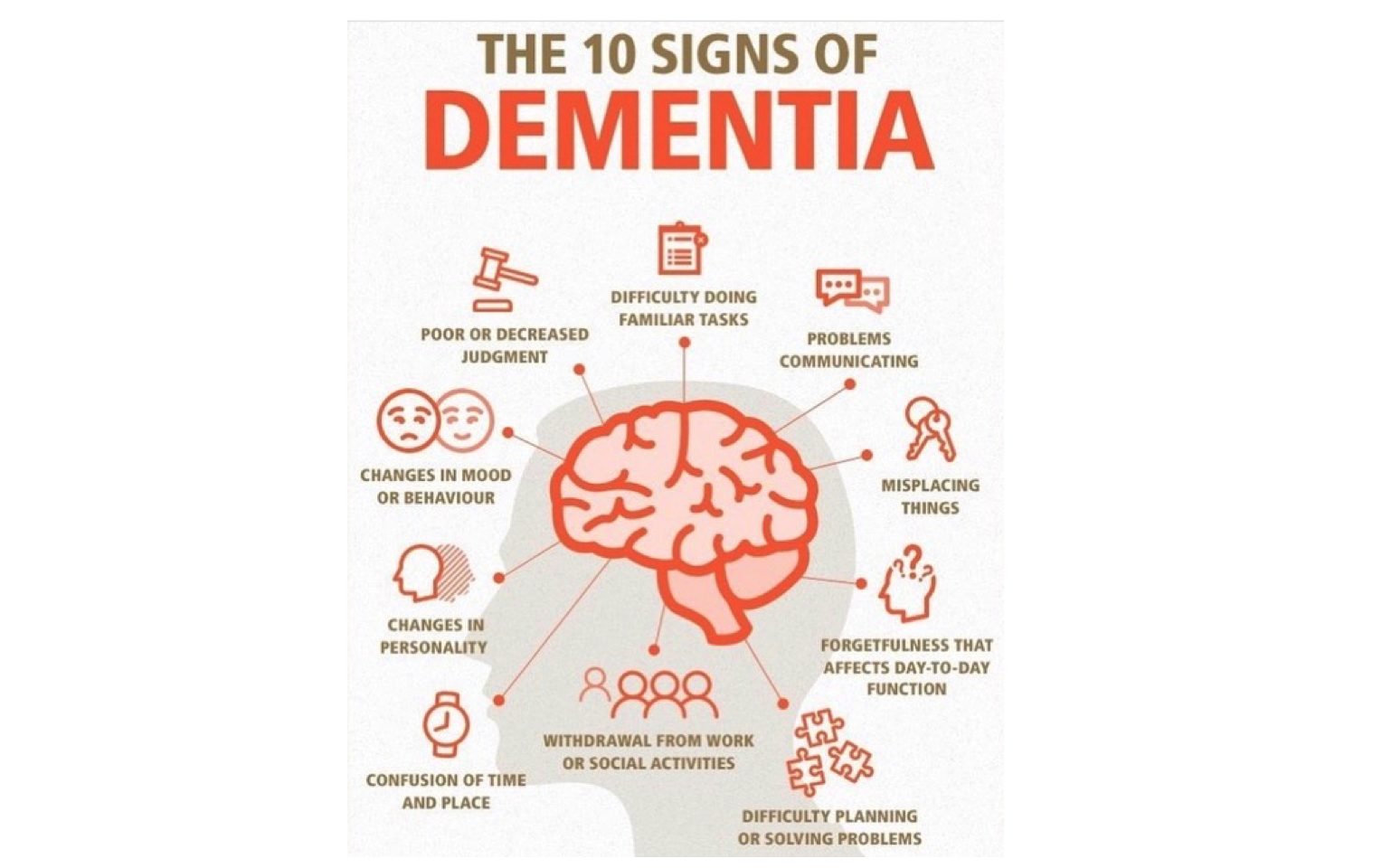

The 10 signs of Dementia

Ten signs of dementia and ten questions you could ask yourself

2. – How long has the person had the symptoms?

3. – Could they normally manage their household and self-care before?

4. – Are their normal personal routines still in place?

5. – Are they forgetting appointments – or medications?

6. – Are they able to make and keep work appointments or social arrangements?

7. – Do they ever get confused as to their whereabouts?

8. – Have you noticed any differences in their dress or behaviour?

9. – Do they seem to be less motivated?

10. – Does the person seem distracted, or vague?

• Reviewing the person’s medication

• Considering referring the person for neuropsychological testing or a geriatric assessment

• Assess other reversible causes/factors of memory loss: CMP, CBC, thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 & folate

• Asking the doctor to arrange an MRI scan.

Listening – a dog’s life

Woof, Woof!

Listening workshops can help care professionals – and us, to listen better. Effective, or Active listening might be described as ‘deliberate listening without passing judgement’. It means reminding yourself constantly that your aim is to truly hear what the other person is saying.

This means parking all other thoughts and setting aside behaviours that might be distracting you and avoiding thinking about your reply, so really concentrating on the person and their message.

The workshops offer tried and tested exercises, games and reflective discussions to help participants listen better.

In subsequent impact measurement, a participant nurse reported that not only his work, but also his marriage had improved as a result; another carer said she was now able to build a detailed care plan for someone with dementia who had no friends or family left alive.

We asked residents to share any outcomes they had noticed. One spoke of feeling more valued, “being listened to makes you feel that what you have to say is worth something”. Sorry, what’s that you said?

Chatterbox groups

Chatterbox Groups

Being listened to matters. People living in care homes need meaningful conversation every much as do we who live independently – it’s part of our wellbeing.

In a care setting, if a person’s dementia is advanced, staff may struggle to engage with them. Few carers have any training in meaningful conversation – added to which, their ages, life experiences and possibly social cultures may be very different.

According to a study by Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Arizona, outgoing, gregarious people who have deep, meaningful conversations also have happier lives. People who spend less time alone and more time talking with others have a greater sense of personal well-being, suggests the study, published in the journal of the Association for Psychological Science. Co-author Simine Vazire PhD, assistant Professor of Psychology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University says, “having more conversation appears to be associated with a greater sense of happiness among the people in the study.” The happiest were those who engaged often in more meaningful and substantive discussions, as opposed to idle chit-chat and small talk.

This finding is also true of people living with dementia. When we value people’s histories, co-incidentally, we help give them a kind of meaningful future. If we fail to listen to their rich life experiences, we fail to value them. Stories of learning how to make do, mend and keep your chin up in challenging times are as relevant now as they ever were. It can be oddly comforting for us to hear the experiences of a person who has ‘come through’ with a longer perspective on life.

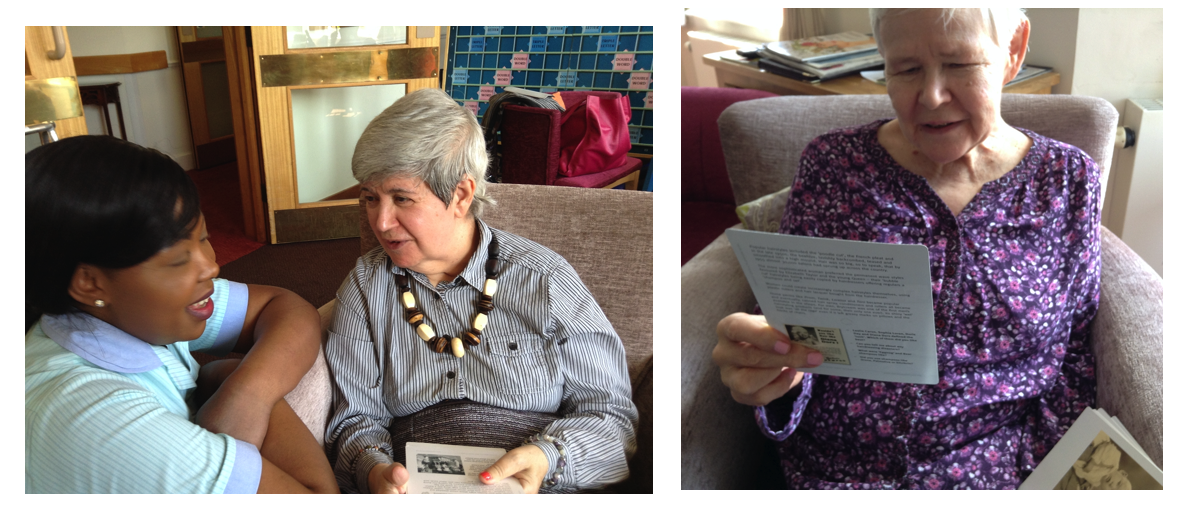

Since 2015, it’s been a privilege to facilitate regular conversation groups with residents at a London care home, based on the principles of REAL Communication (Reminiscence, Empathic engagement, Active listening and Life story) and the Chatterbox cards. The sessions last for about an hour each and take place twice a month. Four or five residents with advanced dementia attend the first group and about ten people with cognitive impairment but whose communication skills are still relatively intact come along to the second one.

A four-month trial proved so successful that they have continued ever since. The stories people have shared have helped us to map their life stories in a way that a more formal assessment simply cannot. Our thoughts, experiences and memories rarely follow a chronological path. In capturing them as they are sprinkled throughout the sessions, we have been able to build a more complete – and interesting picture of each person. This has then been translated into more focussed care.

Chatterbox Groups

Since 2015, it’s been a privilege to facilitate regular conversation groups with residents at a London care home, based on the principles of REAL Communication (Reminiscence, Empathic engagement, Active listening and Life story) and the Chatterbox cards. The sessions last for about an hour each and take place twice a month. Four or five residents with advanced dementia attend the first group and about ten people with cognitive impairment but whose communication skills are still relatively intact come along to the second one.

A four-month trial proved so successful that they have continued ever since. The stories people have shared have helped us to map their life stories in a way that a more formal assessment simply cannot. Our thoughts, experiences and memories rarely follow a chronological path. In capturing them as they are sprinkled throughout the sessions, we have been able to build a more complete – and interesting picture of each person. This has then been translated into more focussed care.

Our favourite toys Smiley and Mrs Pussy

Reminiscing stories of our favourite toys

We all have reminiscing stories to tell about our favourite toys, gathered together from a time when we were younger and smaller. One only has to think of the lovely Grayson Perry and his marvellous teddy bear, Alan Measles.

Well here’s another lovely story, this time it’s Smiley and Mrs Pussy..

Smiley and Mrs Pussy

Smiley is seen here with Mrs Pussy after more than 40 years of love, tears and secrets. He’s wearing the jumper and trousers of my mother’s teddy, “Edward Bear” and was a present from my Granny, bought with Green Shield stamps (my grandparents were very hard up) for my sixth Christmas present.

Mrs Pussy, although a better class of teddy, didn’t hold the same appeal, though she has washed her skirt for the photo and the pair of them have planned their retirement by the sea.

Many thanks to Fi Howard, textile designer, www.fionahoward.com

I loved him more than anything else and would have risked my life for him. He was there for me when I was homesick away at school, when I was ill, needed someone to talk to, or just someone to snuggle up to every night.

Chatterbox Cards and the Memory Café

My visit to the Alzheimer's Society Memory Café

There’s an Alzheimer’s Society Memory Café at a Housing Trust in north London. Everyone who attends is living with dementia, to varying degrees and I’ve been lucky to spend time there with the regulars to facilitate conversation using Many Happy Returns 40s and 50s Chatterbox cards.

My first visit included one family carer and four housing trust staff members. There were about 18 of us in the room, sitting around small tables with oilskin cloths, on each of which was a small glass vase with a single bright yellow fabric chrysanthemum. The colour of hope, I thought wistfully.

Everyone was wearing a badge and as always, we all introduced ourselves. I noted unusual names – most of those present were local, but a few had arrived here from the Commonwealth or as refugees from war. I knew that meant we would likely hear some intriguing stories.

The room was quiet and expectant. My first prompt was to seed thoughts of childhood – toys and games and freedom – adult authority. Tentatively to begin with, the group started sharing memories of favourite toys from childhood. Descriptions of dolls and dolls’ houses, of dolls’ prams and dressing up family pets to wheel around in them, of cap pistols and Painting by Numbers, these soon became stories of constantly being sent outside regardless of the season, (even when unwell) of running around unsupervised, of climbing trees, of innocent ‘gang’ games, and in winter, of mucking about in the (helpfully warm) local tube stations.

One man who said his family could afford no toys at all, described his pet Collie, 'Sailor'. "Rather an odd name for a dog I suppose!"

As often the case, despite their relative poverty, they described lives of happy, unfettered freedom hardly known by children today. One man who said his family could afford no toys at all, described his pet Collie, ‘Sailor’. “Rather an odd name for a dog I suppose!” he laughed, “he never ever went on a boat. I trained him and he was at my side all the time. He would do that thing that Collies do, crouching down to listen. He was really clever.” There was a lady who had grown up in Greece. Her language has reached that stage where her words sound quite feasible but are nonetheless, challenging to understand – or even hear, spoke with poignancy and pleasure about playing with her sisters in the sunshine on her local island beach.

Then we spread the Many Happy Returns Chatterbox cards arbitrarily around the tables. Every group – by now animated and chatting away happily, carried on. As always, prompted by the subjects, pictures and information on the cards, the volume in the room rose swiftly and dramatically as these fascinating older people revealed their histories to one another.

Their memories now spread across the landscape of their lives, their relationships, jobs, children and grandchildren.

As always, the volunteers expressed astonishment at the instant connection prompted by the cards, at the enjoyment and pleasure they observed, and at the sheer amount of conversation and animation. As always, the participants commented on the cards and how well they prompted meaningful memories.

People didn't really want to stop sharing and lingered on beyond the finish time to continue chatting

As always, like all good parties, people didn’t really want to stop sharing and lingered on beyond the finish time to continue chatting.

And as I have often found, as I trudged back to the bus stop, I felt a real sense of satisfaction that the chatterbox cards had once again delivered. Prompting so much fun and excited communication for everyone that day at the Memory Café. I also felt a deep sense of privilege and wonderment to be able to bear witness to their hidden treasure troves of life experience and history.

You can find out more about the the Many Happy-Returns Chatterbox Cards here >

REAL Communication workshops for carers

REAL Communication workshops for carers help develop communication skills through interactive, experiential and blended learning programs.

Facilitating REAL Communication workshops for carers is always a privilege. Being interactive, what happens is always a Quid Pro Quo: a real exchange of learning and experience.

Good communication is absolutely central to good care. Nowhere is this more true than in the care of people living with dementia, for whom there is no cure and almost no palliatives. For family carers and care workers, good communication is vital: they all live with stress, anxiety, loss and grief on a daily basis while the person is still alive.

The REAL Communication* framework and mantra developed to address these issues:

- We cannot care for a person if we don’t care about them;

- We cannot care about them if we don’t know who they are

Care is always a triumvirate between the person being cared for, professional health and social care staff and relatives and friends. As all evidence shows, when these relationships work well together, good care always results. Conversely, if these relationships fail, poor care is inevitable.

Older people who are vulnerable and frail need sensitive relationship-centred care and robust advocacy, especially if they have dementia. They have rich life experiences that can have a deep affect on how they view their relationships with everyone around them – and life in general.

When we have empathy for the person, listen to them well, understand how their memory systems function; when we show kindness and recognise, appreciate, honour and celebrate their life experiences, they are encouraged and empowered to live life more fully, regardless of their condition.

*The REAL Communication Framework

REAL is an acronym for: Reminiscence, Empathic engagement, Active listening and Life story.

All REAL Communication workshops include the REAL framework. This means that any carers attending our workshops will further develop and improve their communication skills and abilities.

The resulting learning outcomes will further encourage the provision of improved communication. This enhances relationship-centred care and delivers improved quality of care received by the person living with dementia.

Our unique approach sits at the heart of the Norfolk & Suffolk Dementia Alliance blended learning programme, recognised by the Performance Learning Institute gold award in 2014.

Image: Will van Wingerden

SCIE have great resources – and here’s why

SCIE have great resources – and here’s why

By Sarah Reed 17 June 2013

I recently tweeted that SCIE have great resources – and here’s why:

We’ve just celebrated Carers Week 2013, and it’s important to remember that getting anything right in meaningful dementia care for a person can be a challenge. The cognition, awareness and linguistic goalposts are continually on the move and the very personal and unique nature of the condition is challenging.

Help is at hand. The lovely people at SCIE have invited me to write this opinion piece after I tweeted “@SCIE_socialcare is probably THE best care resource on the web – excellent in every way! Thank you.”

I really meant it. The resources on the site are extraordinary. Want to know more about reablement? They’ve got it. Need guidance on how carers can work with care staff over dementia care? This is where you’ll find it. Keen to up-skill yourself in co-production? Here’s the seminal advice.

SCIE has gathered a stellar group of care specialists and persuaded them to share their deep experience and knowledge on a wide range of subjects, which any carer can use whether working professionally or in an entirely domestic setting with a family member of friend. This is where you’ll find some of the most expert trainers.

I publish Many Happy Returns’ “conversation trigger” Chatterbox 1940s and 1950s cards for people with dementia; I also run REAL Communication Works™ skills development workshops, to promote better interaction with people with dementia for health and social care care-givers, and University students. The participants are often thirsty for knowledge and it’s great to know that I never need to swamp them with paperwork to support the programme. I just point them in the direction of the SCIE website. Job done –and a few trees saved, into the bargain!

And when writing articles or developing other resources of my own, it’s vital to get it right in every respect, so the SCIE website is my first port of call to check that my point of view is supported and endorsed by the best of the best-practice experts.

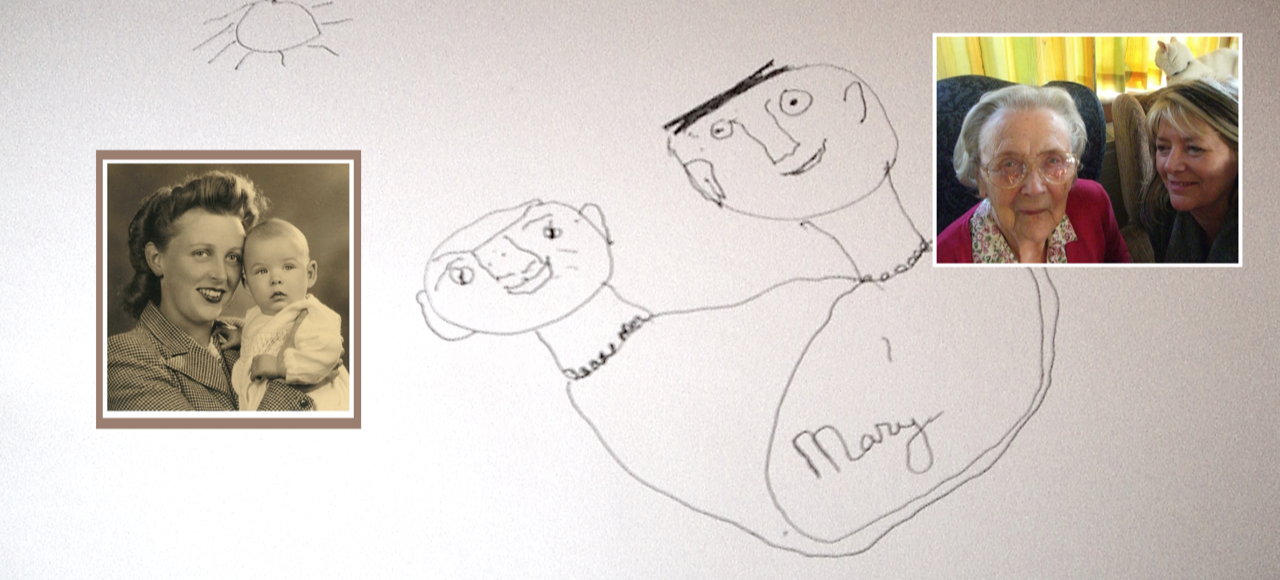

SCIE always remember the people they serve – the people who use services and their carers. It’s good to be reminded and as growing numbers of people are caring for their families at home, this is more important than ever. Here’s the story of one such couple; they happen to be my parents.

My Dad was a stiff-upper-lip kind of man

When a loved one develops dementia, those closest to them are likely to experience feelings of confusion themselves, as well as anxiety, guilt, grief and bereavement – even before the person dies, as the illness progresses.

No sooner do they come to terms with one stage of the loved one’s illness than the person’s behaviour changes again or their cognition declines further and the grieving starts all over again. A sense of loss is one of the most powerful feelings that people experience when someone close to them develops a dementia.

My father spoke about this with me on a number of occasions during the decade that my mother had dementia. Had SCIE been in existence at the time I know how it would have helped us.

He said that not only had he lost the person he had married in 1940, he’d also lost their future together. He missed the years of happy companionship they’d enjoyed, but equally, he was frustrated by the constraints on his freedom.

After three years at home, my 85 year-old mother was admitted to a care home. For my father, whilst relieved, this rendered the family home an empty vessel, with only the ghosts of their former lives for company. Of course my mother’s life was hardly better, coping with an utterly different and mystifying life, in the company of strangers.

My father seemed overwhelmed by sadness and anger. I noticed his underlying resentment and unhappiness that things had not turned out as he hoped. He was lonely and isolated and he worried a lot about the potential cost of ongoing care.

Unable to recognise that he was under a lot of stress and unable to to ask for the emotional support he needed, he would bottle up his feelings. He began to weep openly.

We encouraged him to spend time with friends, but he found it difficult to do things that would normally have included my mother. He tried to muster his old energy, but without his beloved partner of sixty years, he gave up.

A few years on, after a short illness and three years ahead of my mother, he died.

“Who’s in that box?” she asked at the funeral.

Sarah Reed is a dementia communication specialist and trainer; and founder of social enterprise, Many Happy Returns