Talking makes people happy.

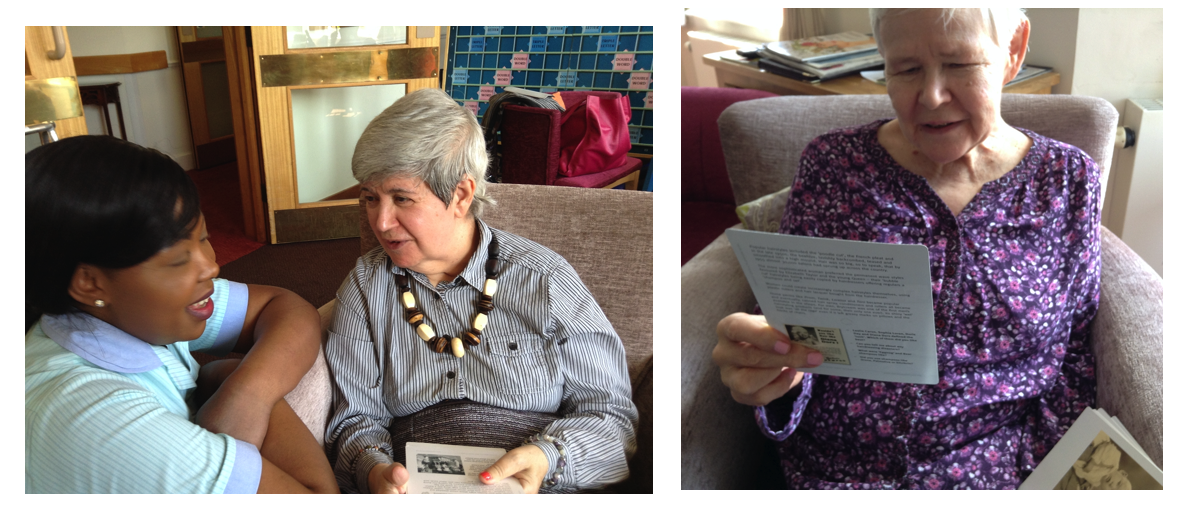

When my mother was in the care homes she lived in for the last seven years of her life, I was keen to ensure that she was engaged in meaningful conversation by carers as much as possible, so that when the family could not be there, she felt stimulated and happy.

She had dementia and I observed was that the more advanced her dementia became, the less staff were likely to engage in conversation with her. Often this was because the younger carers had no training in how to start or maintain a meaningful conversation with a person living with more advanced dementia – and of course, their life experiences were so different. It was this observation that largely prompted me to develop Many Happy Returns conversation trigger cards and REAL Communication workshops.

The workshops focus on a range of communication issues, including overt and unspoken language, body language, voice, tone and inflection, the complexities of memory and how it works, compassion and empathic engagement, why listening is so important to us all and how to do it better and the vital importance of a person’s life story and why it matters quite so much to any older person with dementia as well as those caring for them.

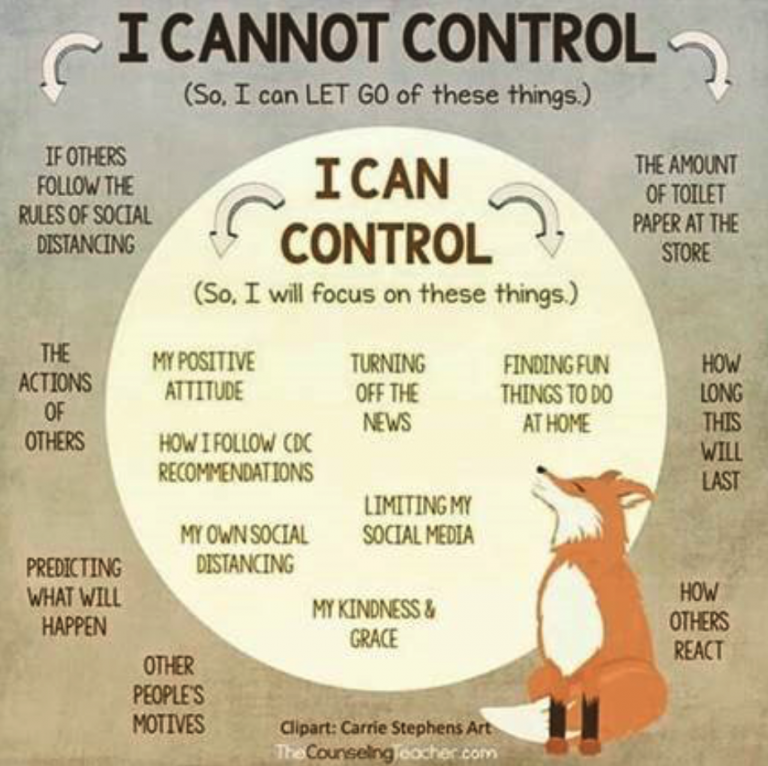

Self-care is part of communicating with oneself and more awareness of this and of self can help reduce the well-documented incidences of professional and unpaid carers’ burn-out.

As far as I know, there are no other conversation trigger cards like ours, which include carefully researched images from social culture with contextual background information and conversational prompts. Our REAL Communication workshops are unique. Both are based on research evidence. The following research results contribute to our work.

According to research from Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Arizona, outgoing, gregarious people who fill their lives with deep, meaningful conversations are lucky to have one of the keys to a happier life.

People who spend less time alone and more time talking with others have a greater sense of personal well-being, suggests the study, published in the journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

“Having more conversation, no matter how trivial, appears to be associated with a greater sense of happiness among the people in the study,”

“Having more conversation, no matter how trivial, appears to be associated with a greater sense of happiness among the people in the study,” co-author Simine Vazire, PhD, assistant professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.However, the happiest people were those who often engaged in more meaningful and substantive discussions, as opposed to idle chit-chat and small talk.

Based on the conversation patterns of 79 college-aged men and women was tracked over a four-day period, the study was conducted by Vazire and three colleagues at the University of Arizona.

Using an unobtrusive recording device that participants carried in a pocket or purse, researchers taped 30 seconds of sound every 12.5 minutes, amassing more than 20,000 audio snippets of sound from the daily lives of participants.

Members of the research team listened to the recordings and coded the number of conversations each participant had, and whether each conversation was substantive or small talk. Each participant’s happiness level was scored using standard psychological tools for gauging personality and wellbeing, including self-assessments and reports from friends.

Participants scored as “happiest” in the study spent about 25 per cent less time alone and 70 per cent more time talking to others, as compared with the unhappiest participants. The happiest participants had twice as many substantive conversations and one third as much small talk as the unhappiest participants.

“Overall, these findings suggest that meaningful interactions with others are important for wellbeing,” Vazire concludes.

“However, our research cannot determine whether meaningful interactions cause happiness, whether happiness causes people to have more meaningful conversations, or whether there is another explanation. We believe it’s likely that both are true – that happiness leads to more meaningful connections with others, which then produce more happiness – but this remains to be tested in future research.”

When we feel valued and appreciated, our sense of self improves and we are more likely to value and appreciate others more and in turn, this encourages them to value and appreciate us more. Nowhere is this ‘virtuous circle’ of value and appreciation more true and more obvious, than in care homes.

To conclude, meaningful conversations need inspiration.

When we inspire a person we are speaking with, we create a welcoming space in which they are encouraged to share, (but not required to). This gives them more freedom in how they respond. If you ask, “How was your weekend?” (an invitation), the person can only respond by answering your question.

Instead, if you share a story from an event you experienced at the weekend that may be relevant to the other person (an inspiration), then they can choose how they respond. It’s up to them. And that means it’s not up to you.

Weaving inspiration into our conversations frees us from the responsibility of knowing what to say next. Inspiration encourages us and the other person to ‘co-create’ a conversation together.

All we need is to be genuine in what we share, and share it in a way that encourages others to share as well.